EXCERPT - The Solidarity Economy is Thriving in Cities

Written by SP subscriptions

An Excerpt from Solidarity Cities: Confronting Racial Capitalism, Mapping Transformation collectively written by Maliha Safri, Marianna Pavlovskaya, Stephen Healy, and Craig Borowiak.

In cities powerfully shaped by racial capitalism and economic exclusion, communities have long fought to reclaim their futures through economic solidarity and cooperation. This has been the case through the darkest stages of racial capitalist urban history and remains crucial in the face of a resurgent patriarchal white supremacy today. Our research reveals a striking pattern: the very neighborhoods redlined into disinvestment and organized abandonment decades ago have become hubs of worker cooperatives, credit unions, community gardens, and mutual aid networks that together constitute the decentralized but vibrant solidarity economy movement.

Iglesias Garden is a racially mixed community garden in a low-income, demographically diverse edge-zone neighborhood of Philadelphia. The garden entrance is marked with signs that welcome visitors and neighborhood residents but warn developers the garden land is not for sale. The welcome and warning clarify the gardeners’ intentions: what they are for and what they are against. The garden, along with its citywide campaign to extend solidarity and transform urban land policy, is a model of what is possible. What we can see in the garden is not so much a world in which capitalism, racism, and other forms of marginalization have vanished but rather a world where they are not the operative logics. Through their daily operations, solidarity economy initiatives, like Iglesias Garden, actively manifest postcapitalist practices rooted in collective principles. These spaces and the people in them work to build, protect, and transform local communities, drawing from diverse traditions and motivated by aspirations for a more livable world.

Taken together, the stories and maps of solidarity economy initiatives destabilize what can often seem like a template of polarized urban development under racial capitalism. Within this template, we find areas catering to the economic and cultural elite. Within the same cities, we also find neighborhoods where poverty affects high proportions of residents, most often people of color, who struggle to meet their daily needs. Between these paired logics of the Gentrified City and the Disinvested City, solidarity economy institutions reveal a third dimension of city life that organizes urban space in a different way, one rooted in the ethics of economic cooperation, inclusion, mutuality, and democracy, and in community struggles for racial and economic justice. We call this third dimension the “Solidarity City.”

We introduce the idea of the Solidarity City to evoke an alternative spatial imaginary where solidarity relations are definitional of urban life. In general terms, solidarity names a sense of collective responsibility and shared purpose that connects an individual to a group or community. To be in solidarity entails both feeling common purpose with others and being willing to make sacrifices. For us, the Solidarity City names something that exists in the present (a diverse economy of cooperation) and can be found in the past (though traveling under other names). It also names an aspirational horizon for realizing more solidarist urban futures. The Solidarity City is thus a concept that harbors past, present, and future tenses. It also extends across multiple social domains and scales of urban life: from volunteering and caring for others to city-wide initiatives. Our focus is on the economic domain and on initiatives, relationships, and practices associated with a burgeoning global solidarity economy movement. This movement (a social movement in which we have each extensively participated) seeks to create an economy for people and the planet and thereby works toward ending the dominance of capitalism. Focusing on solidarity’s role in city-making, this is a study of the enduring imprint of racial capitalism on urban geographies and how solidarity economies are affected by, respond to, and can transform entrenched racial and economic divides.

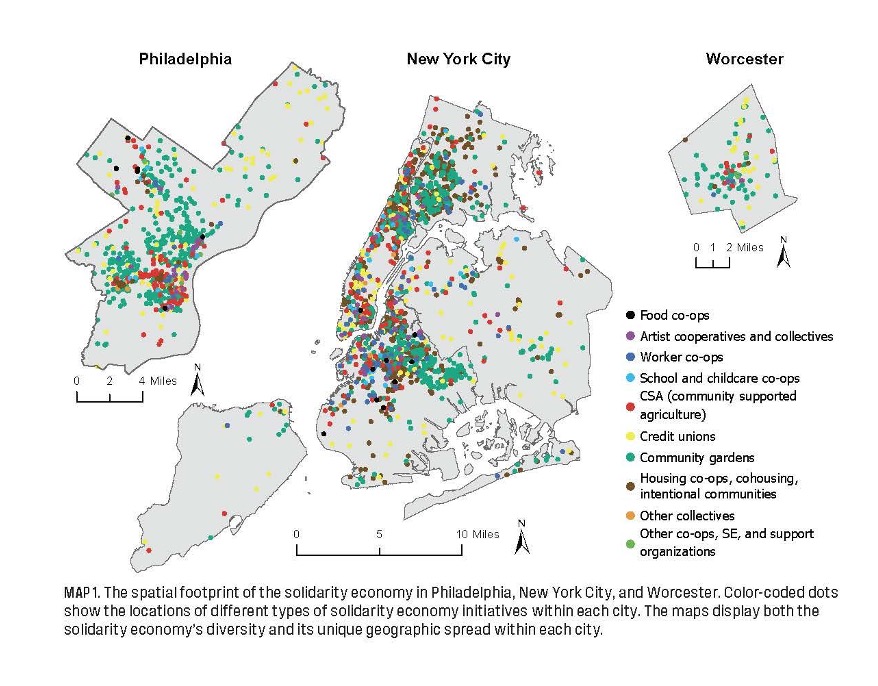

We examine solidarity economies in three U.S. cities: New York City, Philadelphia, and Worcester, Massachusetts, but elements of the Solidarity City exist worldwide, from Cochabamba, Bolivia, to Cape Town, South Africa. Interest in solidarity-based alternatives to capitalism is growing. As community-engaged researchers, we have witnessed remarkable grassroots ingenuity as communities innovate with economic initiatives prioritizing ethics over profit and well-being over individual wealth. Over the past decade, experiments with cooperatives, community-supported agriculture, and community finance have proliferated in response to economic, ecological, and climate crises. Many draw on mutual aid traditions that sustain communities amid systemic oppression.

As important as such initiatives are for many communities, they nevertheless typically fall out of mainstream studies of the economy, which focus instead on for-profit enterprises, capitalist markets, and state budgets. Moreover, to the extent that such initiatives are studied, they have generally been treated in isolation from one another. Thus, consumer cooperatives are studied independently from worker cooperatives, which are studied separately from community gardens, credit unions, and so forth. This piecemeal approach reinforces what J. K. Gibson-Graham term a capitalocentric worldview, which a priori asserts capitalism as the dominant (if not singular) form of economy, while alternatives are presumed to occupy only small niches in society and are accordingly pushed to the periphery, to the extent they are acknowledged at all. For those looking for a way beyond capitalism, possibilities become difficult to imagine under such a worldview.

We counteract these limiting habits of thought by exploring the geographies that emerge when diverse initiatives are brought out of their silos and conceived together as facets of a shared solidarity economy capable of transforming cities and ways of urban living. What if we could learn to see the examples all around us not as scattered exceptions but as constitutive elements of the vital networks of human solidarity that support urban life? What if, amid the towering trees of capitalist structures that seem to dominate our horizons, we could sense an expanding solidarity ecosystem growing in the understory and composing the Solidarity City? We would see vibrant life in the forest—many other trees, as well as bushes, ferns, mushrooms, etc.—that might be considered non-capitalist forms nurtured by solidarity flowing through the underground root systems like the fungi symbiotically connecting trees. Visible above ground are the more formally organized parts of the Solidarity City—housing and worker cooperatives, credit unions, community gardens, and more. Below ground, the undercurrents of solidarity spread through the soil, nurturing informal economies and social practices, while sustaining what lies above through goodwill, reciprocity, and care. Learning to see the solidarity already operating within economies is a crucial step toward envisioning what solidarity cities have been and might become.

The solidarity economy has played multiple roles in urban neighborhoods as a long-term survival strategy, a means of collective resistance, and a non-capitalist mode of world-building. We analyze the geographic patterns that the solidarity economy forms across cityscapes through a series of maps. We consider this approach to be a strategy of counter-mapping that has ontological power to produce urban realities. Making solidarity economies visible on the maps leads us to recognize their role as urban processes that contribute definition to cities as we know them today. It also helps us understand how the gentrification, organized abandonment, and other dynamics of racial capitalism have patterned practices of solidarity.

In these lights, three central contentions organize our thinking. Our first contention is that the scale of the solidarity economy is bigger than commonly thought.

Second, we argue that many of the race and income divisions that underlie modern urban life in the United States—and that we call fault lines—are also manifest within the geographies of the solidarity economy.

Third, following from this observation, we contend that solidarity economy initiatives and the movement at large, while being affected by these racial and economic divisions, themselves possess many of the normative and practical resources for confronting and ultimately transforming these fractured landscapes. The cities we study provide abundant examples of non-capitalist initiatives working toward racial and economic justice by means of trial and error, experimentation, failure, setback, and persistence. These offer, using the words of Ruha Benjamin, a practical toolbox of beautiful experiments capable of spreading justice rather than toxicity from one place to the next. In all those instances, solidarity economies build livelihoods, defend them, and resist the workings of brutal racial capitalist forces, all the while building pathways to cities of the future made for people and the planet.

The three propositions correspond with what we might identify as different readerships, as indicated in the following map.

For practitioners, our book is a reminder that both the solidarity economy and the possibilities of the Solidarity City exist in a social context that is marked by divisions, what we call race and poverty fault lines, that also structure urban reality. And for the committed, we offer a shared hope that the solidarity economy possesses the normative commitments to engage in a politics of postcapitalist transformation. We understand this hope not as an unquestioning faith but rather as one that is grounded in what we have found—efforts in each of the cities of solidarity economy initiatives trying to live up to the name of solidarity.

Patterns in the City and the Politics of Solidarity

The solidarity city does not emerge in a vacuum. All three cities provide unique contexts that shape the emergence of solidarity economies. Yet across that difference, throughout the book we present evidence on how different spatial patterns in the distribution of solidarity economies define the shape of the solidarity city in each place. Looking at community gardens and community supported agriculture, we identify fault-line patterns of race, poverty, and wealth that run through solidarity economies, much as they do urban life more generally. Looking at worker cooperatives, housing cooperatives, and credit unions, we also identify “bulwark patterns” where communities defend themselves against racial capitalist forces of exploitation, displacement, and predatory finance. And we identify convergences of solidarity economies in neighborhood edge spaces where people encounter one another and extend the bonds of solidarity across fault lines of race and poverty—a form of edgework that connects communities, forming what we call an ecotone pattern. Cooperatives in Philadelphia are an excellent example of the edge-zone/ecotone pattern.

Inhabiting Urban Ecotones: Cooperatives in Philadelphia

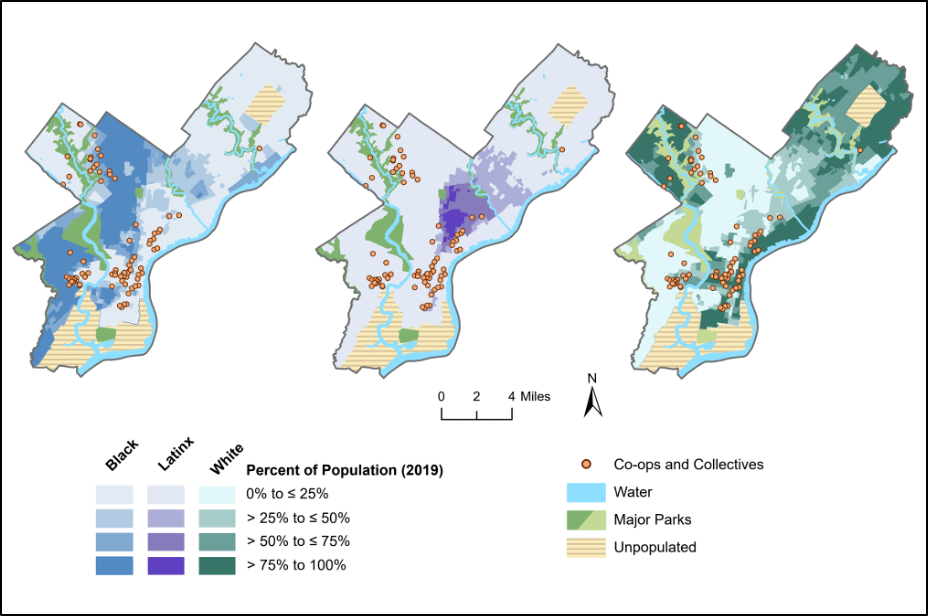

The social significance of cooperatives is tied not only to what co-ops do but also to where they are. What can the location of cooperatives in Philadelphia teach us about cooperatives’ transformative potential? We focus our attention on worker cooperatives, housing cooperatives, consumer cooperatives, artist cooperatives, and a variety of volunteer collectives.

Mapping cooperatives against race and income variables shows that Philadelphia cooperatives cluster in mixed neighborhoods sandwiched between more segregated areas. This edge-zone or ecotone pattern is not one we deliberately set out to map at the onset of this project. It emerged as a photo negative, only becoming visible to us in relation to the spaces where cooperatives are absent. This becomes evident when we map the distribution of cooperatives against Black, Latinx, and white populations.

Philadelphia’s racial segregation stands out sharply in these maps. Few cooperatives can be found in the large expanses of the city with a three-quarters Black majority. Moreover, almost all of those that are present in such neighborhoods fall along the edges. It is as if the cooperative sector skirts the boundaries but is rarely located in the heart of Black neighborhoods.

Similar patterns are found within Latinx neighborhoods, which are about as starkly segregated as the predominantly Black neighborhoods are, though the scale of the Latinx neighborhoods is smaller. The Latinx population is quite visibly concentrated in the Kensington region of North Philadelphia, one of the lowest-income areas of the city. Strikingly, cooperatives are almost entirely absent from those neighborhoods. Once again, they reside along the edges.

By no means should this be read to imply that Black and Latinx populations are not participating in Philadelphia’s cooperatives. That is emphatically not the case, as is evidenced by the composition of members and missions at co-ops old and new. There is a long history of economic cooperation and mutual aid within Philadelphia’s Black community. And by many measures, Black and Latinx leadership and involvement have been central to the city’s contemporary cooperative movement.

What might be going on here?

We more closely examine the dynamics of cooperatives in three edge-zone neighborhoods in Philadelphia: Germantown/Mount Airy, West Philadelphia, and Kensington.

In ecology, the concept of ecotone is used to describe transitional ecosystems that are known to have especially rich biodiversity. We adapt the concept to describe culturally rich transitional neighborhoods in otherwise divided cities. While ecologists would consider both a mangrove forest and an estuary as examples of transitional ecotones, they also recognize that such areas differ from one another. By analogy, while we can observe that co-ops cluster in edge zones, we should not assume that all edge zones are the same. Indeed, what emerges from our research in Philadelphia are three very distinct neighborhoods with different edge-zone dynamics. In one case (Germantown/Mount Airy), we find a remarkably stable neighborhood that has intentionally sustained itself as a racially diverse, middle- class community over several decades. In a second case (West Philadelphia), we find a more demographically fluid activist neighborhood that has undergone multiple reversals in its racial and economic trend lines over the last half century. There, recent gentrification is only one part of a tumultuous history of demographic change. Only in our third case (Kensington), do we find a more classic model of gentrification at work where rising rents and prices are driving former residents out and where there is a very sharp divide between gentrified and non-gentrified spaces. These findings challenge the notion that gentrification is inevitable, as these three ecotones suggest otherwise. What can we learn from neighborhoods that maintain race and class diversity? How might cooperatives and the solidarity economy contribute to making neighborhoods and communities that work for all and in the long term?

Copyright 2024 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota. Published with permission of the University of Minnesota Press.