Winter 2020

Reentry: Reintroducing criminal offenders back to society after they did their time

Written by Nuno Solano de Almeida and Avionta Ellis

A brief overview of the current state of Reentry in Little Rock, Arkansas.

“Research shows that when people who have served their time hit insurmountable barriers to finding employment, housing, food, and healthcare, they are likely to re-offend to survive”, - Prison Fellowship VP Advocacy & Legal Kate Trammell (Trammell, 2024)

Historical Background of Reentry

“Reentry” was President Bush’s Faith-based and Community Initiative program to help released ex-offenders find jobs, avoid a relapse into criminal activity, and make a fresh start after jail.

In a country where more than one in two American adults have an immediate family member who was or is incarcerated (Enns, et al., 2018), over 70 million Americans have a criminal record, and on average 650,000 are released from jail every year (NCSL, 2023), all this puts a great strain on the Justice system, as folks continue to be locked in a vicious cycle of exclusion, many continue to fall back into crime.

President George W. Bush first launched the President’s Prisoner’s Reentry Initiative (PRI), coupled with a $300 Million appropriation. The original idea was to help increase public safety by providing resources and support in four different areas that could help improve the quality of life and the outcome of individuals reentering society after incarceration.

The PRI initiative eventually became HR 1593 and was signed into law by the President in 2007. Subtitle C, Chapter 1 established a federal reentry initiative to help prepare prisoners at release and a successful reintegration into the community.

A decade later, in 2018 the First Step Act was signed to reauthorize and expand the Second Chance Act of 2007 to include an early release program for elderly prisoners, and more support for local detention facilities to join forces with nonprofits, including faith-based and community-based service providers, to help reduce recidivism.

To help support the creation of effective reentry models running between departments of corrections and nonprofits all across the country, The US Council of State Governments (CSG) launched the CSG Justice Center, designed to help officials from all 50 states develop the strategies that break the cycle of incarceration, and lift barriers to behavioral health services, economic mobility, and homelessness.

Reentry is a data-driven alternative approach to public safety that aims to connect individuals to communities, that ultimately makes communities safer.

More than 40 states are currently using data-driven alternative approaches to public safety, such as more effective community supervision and community-based treatment services that make communities safer and reduce criminal justice spending.

In Arkansas, CSG Justice Center developed a data-driven framework to assist more than 58 counties in the state to reduce the number of people in jail struggling with mental illness and it brought together policymakers to meet face-to-face and participate in a series of public initiatives, encouraging them to gain a deeper understanding of what challenges people involved with the system encounter (Moore, 2024).

How is reentry working in one state, Arkansas, to stop returning citizens from reoffending?

Arkansas has the third highest rate of incarceration in the country, and it also struggles with high recidivism rates. Forty-six percent of people who get released from the Department of Corrections in Arkansas return to incarceration within 3 years, the large majority due to supervision revocations, or technical violations such as failure to pay parole fees; moreover, its prison population is expected to grow by 1.4% every year (ADC, 2022).

In the spring of 2023, state leaders in Arkansas joined forces with CSG. Together they launched a Recidivism Reduction Task Force to help understand what causes, and how to safely manage Arkansas’s high recidivism rates and its potential impact on crime.

Four Crisis Stabilization Units in Arkansas (CSU) launched by Governor Asa Hutchinson in March 2017, were all fully operational by 2023, tasked with diverting people with mental illness to local treatment, and away from county jails; training parole board members on best practices in parole decision-making; coupled with the use of a new sanction and incentive system for violation of probation and parole.

Throughout 2024, CSG will work with Arkansas’ Recidivism Reduction Task Force to develop and present data-driven recommendations on supervision practices and the availability of behavioral health and reentry services across the state. Their findings will be released for the 2025 legislative session.

One early example of a local successful reentry program is UALR’s School of Criminal Justice “Community Based Reentry Initiative Program”. A joint effort by volunteers from the University of Arkansas and the Arkansas Department of Corrections (ADC), consisting of a peer interaction program with mentors who were once formerly incarcerated. It was found that participants are 15% less likely to recidivate or return to the prison system after they participated in the program (UALR, n.d.).

Federal grants provide funds to states for reentry programs and the state partners with community and faith-based organizations to provide additional reentry services.

Even though there were some significant cuts in public spending on some key criminal justice programs since last FY2023, (including a six percent cut on the Second Chance Act FY2024 reauthorization bill), starting from 2007 at least 49 states and US territories have been the recipients of more than 1,100 Second Chance Act grants, serving more than 400,000 ex-offenders (OJP, November 2023).

Even though the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) points out that Second Chance federal funds have increased over the last few years, indicating recognition for the impact of state-based reentry programs in connecting individuals with communities, programs, and ultimately also reducing recidivism, federal grants are by their nature “subject to political priorities, and because of that may not always be consistent or reliable” (NCSL, June 21, 2023).

Arkansas Department of Human Services has no current Second Chance Act Youth Reentry grants.

According to The National Reentry Resource Center (NRRC, July 2023), Restore Hope (together with Goodwill Industries of Arkansas Inc.), and The Arkansas Department of Community Correction are currently Second Chance Act (Bureau of Justice Assistance) grant recipients.

The American Indian Center of Arkansas, County of Washington, County of Sebastian, Ambassadors for Christ Youth Ministries, and previously also UAMS are all SAMHSA grant recipients.

Community College of the University of Arkansas, Family Health International, Structured Employment Economic Development Corporation, and Little” Rock City” Workforce Development were all Department of Labor (DOL reentry) grant recipients.

Some of Arkansas state reentry legislation and reentry initiatives include: Arkansas Division of Correction (ADC) public contracts with Residential Re-Entry Centers, or Halfway Houses, to provide voluntary faith-based and non-faith-based spiritual treatment to both male and female prisoners nearing release; UALR, Community Based Reentry Initiative Program (CBRIP) utilizing peer interaction with mentors who are incarcerated; City of Little Rock “Sidewalk Program”, hiring trainees for nine-month long entry-level positions within City Departments; Our House Shelter in Little Rock, and Reclamation House in Jonesboro Reentry Services for Women.

Educating the American public to support reentry

“Changing how we think about people in our justice systems is the first step to opening doors for second chances in our communities”, says Ana Zamora, CEO of Just Trust (2024).

Prison Fellowship and Just Trust, two of the nation’s most impactful second-chance nonprofit advocacy groups for criminal justice reform, agree that “the critical work starts with changing what we have misunderstood (…) for decades we ‘ve been told people who end up arrested or incarcerated are inherently bad” (Prison Fellowship, April 2024).

After Prison Fellowship first launched Second Chance Month April in 2017, multiple US presidents and 25 different states, including Arkansas’ Governor in 2019, recognized and proclaimed Second Chance Month. More than 800 organizations, congregations, and businesses have since joined Prison Fellowship Official Second Chance Month partners. Second Chance Month is an example of how millions of people became aware about the barriers faced by people with criminal records and how to unlock second chances for people who deserve a second chance to make their lives right, even if they are imprisoned.

On April 1st, 2024, President Biden proclaimed April as “Second Chance Month,” after Prison Fellowship Ministries first adopted the date to raise awareness and help improve public perceptions of people with criminal records in America, encourage second-chance opportunities, and advocate for criminal justice reform.

Can Anyone Get a Second Chance? Eliminating Barriers to a Successfully Reentry.

While there is growing consensus that giving the formerly incarcerated an equal opportunity to obtain healthcare, housing, education, and consideration for small business loans does empower them to chase their dreams and fuel the economy, there’s now also a realization that drug treatment, mentoring, and transitional services do not always entirely meet the individual needs of recently released ex-offenders as they transition back to society.

An extensive body of research shows that reentry is not a one-size-fits-all, and how programs and services should be tailored to an individual’s unique needs to the extent possible.

Director of the National Institute of Justice Nancy La Vigne highlighted the idea that reentry support services should consider the whole person when preparing individuals for reintegration into the community (NIJ, 2023). Educational attainment, mental and physical well-being, both can improve specific outcomes, but only addressing one issue at the expense of others may not produce the intended impact to facilitate a successful return.

The NIJ outlined the importance of looking at reentry processes like in a continuum that starts in confinement and continues after release. Best practices and successful reentry strategies include an “organizational coaching model” cultivating a positive and supportive relationship between clients and community corrections officers, “sufficiently flexible” to include diverse experiences, backgrounds, and identities of those leaving prison (National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2022).

From a public safety perspective, The Arkansas Division of Community Corrections (ACC) recently released published guidelines for the creation of a community-based coalition “Serving Justice,” inviting all interested parties and stakeholders, including state and local policymakers, but also volunteers, and collaborators within a local community, to sign up with ACC’s proposed organizational structure, and to work together to eliminate the barriers to a successful reentry by coordinating programs and services within the correctional system with the appropriate resources and service providers out in the community (Arkansas Department of Corrections, 2010).

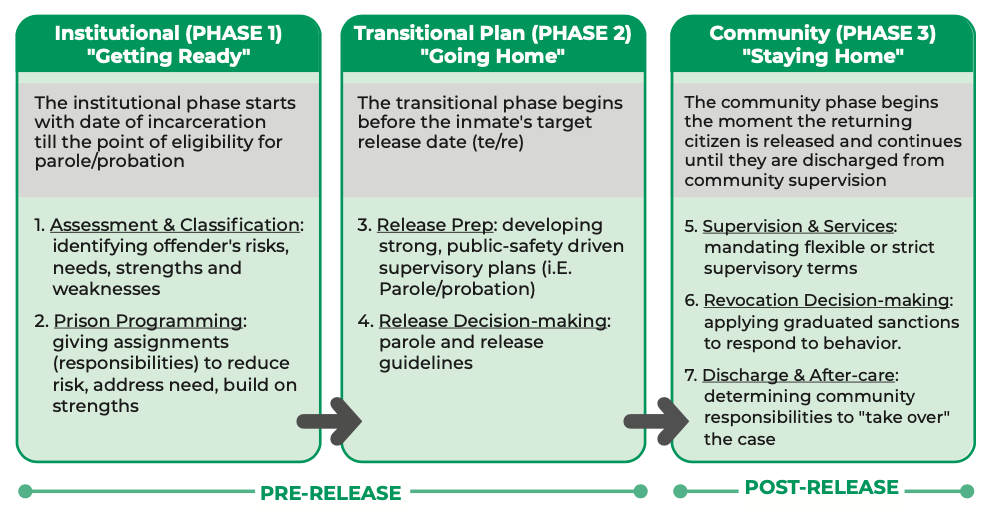

ACC’s goal with a community-based coalition is to remove different barriers to a successful reentry by addressing an ex-offender’s individual needs across all three phases of reentry.

- Pre-Release (Phase 1)

- Post-Release (First 72h or Phase 2)

- Transitional Plan (Phase 3)

This is broadly consistent with other US states’ institutional idea that any successful reentry strategy should focus on the individual needs of returning men and women who also have to overcome different barriers to a successful reentry based on where they are at the moment (“Institutional”, “Transitional”, “Community” as per DOC at Louisiana Department of Corrections).

Faith-based and non-faith-based Community-based service providers’ role is to work with both Correctional systems and clients. However, Community-based service providers ultimately also have the freedom to pick and choose their clients based on their ability to predict recidivism and changes related to recidivism during confinement using a risk assessment tool to determine when an individual grades low, medium, or high on their likelihood of recidivating.

The reentry client, while incarcerated or released under supervision, plays an active role, long before their release date is even set, they’re actively involved at an early stage with the planning for meeting their reentry needs, identifying and addressing their criminogenic risks, and even helping reentry programs and practitioners identify opportunities to enhance their programming and services.

Risk Assessment and recidivating factors. What are the criminogenic risk factors, and what are the predictors of success? What has worked, and what has not?

Title I of the 2018 First Step Act mandated the development and adoption of a risk and needs assessment tool for people in federal custody. Consequently, the National Institute of Justice created the Prisoner’s Assessment Tool Targeting Estimated Risk and Needs (PATTERN, 2021), to assess an individual’s risk of engaging in crime after being released. PATTERN showed high predictive accuracy of recidivism, but not across racial, ethnic, and gender groups (NIJ, 2022).

Arkansas Community Correction Community-based Coalition Handbook recommends correctional facilities “conduct an assessment screening” to help identify inmates’ “prevalent needs” during “phase one” (Pre-release).

Not only incarceration facilities, courts, or parole and probation offices, but reentry Community-based service providers, including Our House in Little Rock, utilize risk/needs assessment tools, as part of their intake and onboarding process.

Conducting pre-post assessment screenings, helps reentry practitioners predict the likelihood of a client’s future outcome based on existing data, and make informed decisions about pre-trial release, failure to appear in court, sentencing, supervision, and treatment (Stein, Pranschke, Pasternak, 2023), as well as to predict clients’ likelihood of recidivism, or relapsing into criminal behavior.

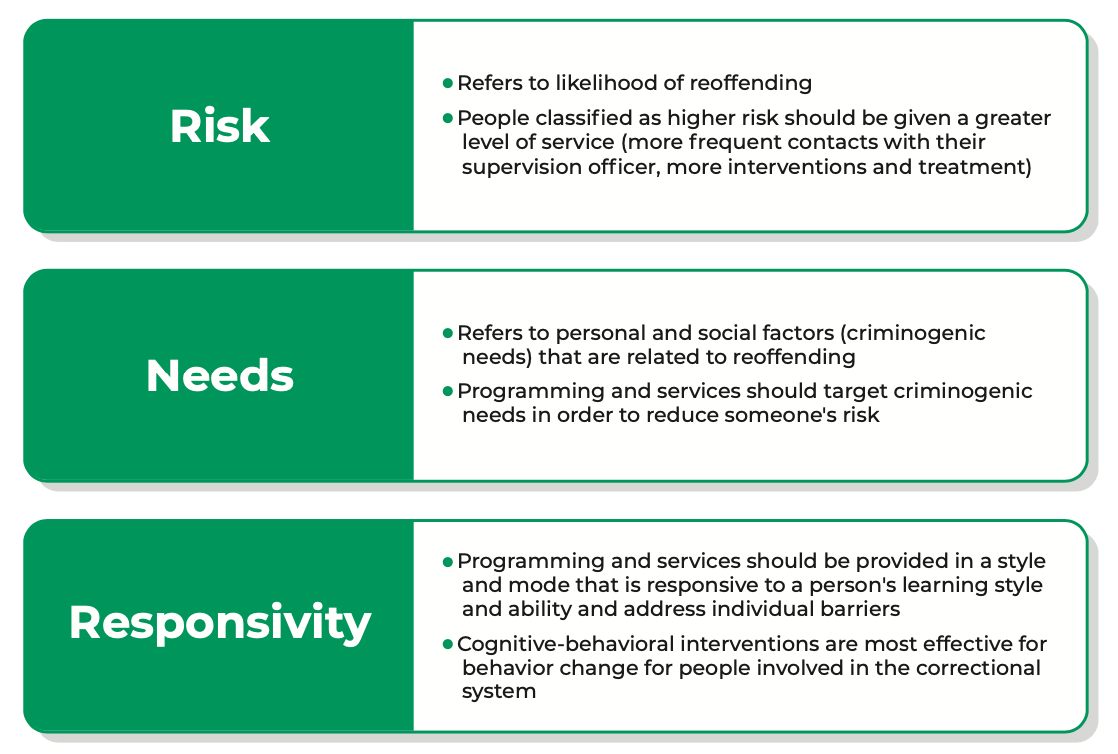

Prior criminal history is a risk that never goes away, except when records are expunged, sealed, or age out. On the other hand, risk factors that do change are called criminogenic risks and these can improve or deteriorate largely depending on the quality of the reentry services available.

Risk assessments therefore are used to generate a dynamic picture of an ex-offender’s criminogenic risks (i.e. employment instability, substance use patterns, etc.). That picture can help predict recidivism, identify their reentry needs, as well as their eligibility for any reentry services during the time of their participation in the reentry program.

Criminogenic risk level categories typically range from low to medium-high risk, the higher the risk the higher the likelihood of recidivating, or in other words: individuals in higher risk level categories average higher recidivism rates. Conversely, individuals who can change their risk scores and levels during confinement, or within three years following their release from custody, are less likely to recidivate.

A large body of research on correctional interventions suggests that cognitive-behavioral treatments, such as “reasoning & rehabilitation” are associated with reductions in criminal recidivism scores across both high and low criminogenic risk groups, because cognitive-behavioral programs address most attributes related to criminal behavior, such as impulsivity, maladaptive patterns of thinking, antisocial and poor social skills, and drug abuse (NIJ, 2022).

In addition to cognitive-behavioral foundation other program elements with empirical support in reducing recidivism include employment assistance, housing assistance, drug education, and relapse prevention, among others.

Evidence shows that risk analysis, combined with needs assessment and a third variable called “responsivity” together provide a more accurate picture of a client’s reentry needs, and potentially lead to more favorable outcomes. There’s a growing consensus that treatment programs should be delivered consistent with the ability and learning style of the participant, not just the predictive risk of reoffending (Pranschke et al, 2023).

According to DOC’s FY22 Annual Report, the 36-month return rate for Arkansas’ Division of Corrections 2017 release cohort was 47.8%, and 37.5% for Arkansas’s Division of Community Corrections, the majority receiving a probation sentence after 19 months, showing that re-incarceration is more likely for supervised individuals than for those who discharged their sentences.

Almost 89% of all prison admissions to Arkansas in 2021 were due to a failure to comply with supervisory terms and conditions, testing positive for drugs, or failing to pay any fines or fees.

Currently, Arkansas ranks fifth in recidivism and violent crime rates in the nation, which prompted the legislature to launch the Legislative Recidivism Reduction Task Force in 2023, charged with developing evidence-based recommendations to improve the outcomes for those reentering the community on supervision.

Conclusion:

The definition of “recidivism” in the Arkansas Code Annotated (A.C.A.) § 5-4-101 is the “criminal act resulting in rearrest, reconviction, or return to incarceration anytime during a three-year period after release from custody.” Recently amended to include probation impositions within those 36 months after release.

According to the latest Annual report released by the Arkansas Department of Corrections in 2022, of 10,795 individuals released in 2017, 46.1% recidivated within 36 months, and more than half had been re-incarcerated 13 months after their release. More than half of those who returned for drug-related crimes were serving time for a drug-related offense before their release.

Considering that 92% of all offenders in custody in Arkansas will one day be released back into their communities (ADC, April 29, 2022), the purpose of all reentry programs is to prepare ex-offenders to return safely by carrying out their court-mandated orders.

Reentry is an evidence-based rehabilitating solution geared towards giving ex-offenders the tools they need to overcome disadvantages and take back their place in society.

Every recidivism study prepared by the Arkansas Department of Corrections since 2016 shows that around half of those who recidivated after their release into the community were due to a parole violation, and so the likelihood of recidivism among supervised individuals is exponentially higher than for those who discharged their sentences.

Whether this pattern shows that supervisory practices require a new and improved set of guidelines and revocation sanctions, or whether community-based service providers should start working closer with community supervision staff, in this short paper we discuss some of the risk assessment tools currently used to align supervision conditions with returning citizens’ risks and needs.

The risk-need-responsivity model of offender assessment and rehabilitation goes beyond the typical case manager’s assessment of criminogenic needs and risk factors; they aim to establish warm, respectful, and collaborative working relationships with the clients that bring out the client’s strengths and other attributes that can make the client feel more empowered.

Research shows that when all three principles of risk, needs, and responsivity are present in the planning for rehabilitation treatments then recidivism rates drop in either custodial, or community settings.

Data-driven alternative approaches to public safety help ex-offenders meet their reentry needs and address criminogenic risks. Reentry strategies that balance supervision requirements with more positive and supportive relationships, and put less emphasis on technical violations, help predict recidivism. According to the NIJ, in 2023 recidivism may no longer be an effective indicator to describe the way a returning citizen is coping after they are released from custody, especially when the risk of arrest can vary by jurisdiction and by demographics (April, 2023). There is growing consensus among the reentry and public safety communities that addressing an individual’s criminogenic needs can improve specific outcomes but may not be enough to reintegrate that individual into the community. On first analysis, to engage returning citizens in their assessments, the planning, and the process of change, motivates the individual to participate in the program and become personally invested in those goals that are so much more meaningful to them. Transition teams, collaborative case management and supervision throughout all three phases of reentry to include the returning citizen, their family members, prison, and community supervision staff, and community-based service providers, may be a successful reentry strategy for both the state and community reentry stakeholders that focuses on the individual needs of returning men and women who also have to overcome different barriers to a successful reentry based on where they are at the moment

Pending any new findings from Arkansas’ Recidivism Reduction Task Force in 2024-25, local community-based service providers will continue to help second-chance citizens reintegrate in Greater Little Rock.

Nuno Solano de Almeida is AmeriCorps VISTA assigned to Our House Career Center

Avionta Ellis is Lead Reentry Case Manager at Our House and Liaison with Arkansas Workforce “Rock City” Reentry

Bibliography:

Arkansas Department of Corrections Division of Correction (2022, March 22) “Embracing Your Community: A Guide to Reentry” doc.arkansas.gov. Retrieved: Reentry-Handbook-2022-A.pdf (arkansas.gov)

Arkansas Department of Corrections (2022, April 29). “Recidivism in Arkansas: a Roadmap to Reform”, doc.arkansas.gov, retrieved: Recidivism-in-Arkansas-A-Roadmap-to-Reform-April29_2022-single_BOC_FINAL.pdf

Arkansas Department of Corrections (2010, October) “Arkansas Community Correction Community Based Coalition Handbook – ACC Serving Justice”. Doc.arkansas.gov. Retrieved: Community_Based_Organization_Handbook_-_012019.pdf (arkansas.gov)

American Institutes for Research, Corrections and Community Engagement Technical Assistance Center (CCETAC). Retrieved: Checklist of Practices for Effective Reentry | National Reentry Resource Center

Bureau of Justice Assistance (May 5, 2018) Collaborative Case Management and Supervision- A Case Planning and Management Model for State and Community Reentry Stakeholders. BJA SRR Planning Grant: Attachment N. 1.A.12 LAPRI Framework Policies and Summary. Pp. 37-42. Retrieved: LAPRI-Framework-Policies-and-Summary-42-pgs-v6.1.18.pdf (socialworx.org)

Enns, P., Yi, Y., Comfort, M., Goldman, A., Lee, H., Muller, C., et al. (2019). What Percentage of Americans Have Ever Had a Family Member Incarcerated? : Evidence from the Family History of Incarceration Survey (FamHIS). UC Berkeley. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/2378023119829332 Retrieved: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/03k8q9t2

H.R. 1593. 110th Congress (2007-2008), Second Chance Act of 2007: Community Safety Through Recidivism Prevention or the Second Chance Act of 2007. HR 1593, 110th Congress (2007): https://www.congress.gov/bill/110th-congress/house-bill/1593

Moore, M., (2024, May, 21), “Arkansas Launches Justice Reinvestment Initiative to Better Understand and Address Recidivism Drivers and Reentry Barriers”. CSG Justice Center The Council of State Governments. Retrieved online: https://csgjusticecenter.org/2024/05/21/arkansas-launches-justice-reinvestment-initiative-to-better-understand-and-address-recidivism-drivers-and-reentry-barriers/

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2022), “The Limits of Recidivism: Measuring Success After Prison”. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26459.

NCSL, National Conference of State Legislatures (2023, June 21), “Successful Reentry: Exploring Funding Models to Support Rehabilitation, Reduce Recidivism. NCSL: https://www.ncsl.org/civil-and-criminal-justice/the-importance-of-funding-reentry-programs

National Criminal Justice Reference Service, U.S. (1987) National Criminal Justice reference Service NCJRC. United States [Web Archive], Retrieved from the Library of Congress: https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/omnibus-crime-control-and-safe-streets-act-1968#:~:text=The%20Omnibus%20Crime%20Control%20and,at%20all%20levels%20of%20government.

National Institute of Justice, (2023, April 26), "Five Things About Reentry", nij.ojp.gov:

https://nij.ojp.gov/topics/articles/five-things-about-reentry

National Institute of Justice, (2022, April 19), "Predicting Recidivism: Continuing To Improve the Bureau of Prisons’ Risk Assessment Tool, PATTERN,". nij.ojp.gov:

https://nij.ojp.gov/topics/articles/predicting-recidivism-continuing-improve-bureau-prisons-risk-assessment-tool

National Reentry Resource Center (n.d.). Public Safety Risk Assessment Clearinghouse PSRAC. U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs, retrieved: https://bja.ojp.gov/program/psrac/selection/tool-selector

National Reentry Resource Center (2023, July). National Reentry resource Center NRRC– State Profile. Retrieved: NRRC State Reentry Supports - Arkansas (nationalreentryresourcecenter.org)

National Reentry Resource Center (2022, April 4) “Effective Practices: Removing Barriers to a Successful Reentry – 2022 Second Chance Month”. National Reentry Resource Center. Retrieved: Effective Practices: Removing Barriers to a Successful Reentry (nationalreentryresourcecenter.org)

Nelson, J. (2024, March, 13), “Biden Signs Six-Bill Spending Package Funding Key Criminal Justice Programs”. CSG Justice Center The Council of State Governments. Retrieved online: https://csgjusticecenter.org/2024/03/13/biden-signs-six-bill-spending-package-funding-key-criminal-justice-programs/

Prison Fellowship, (2024), “Second Chances After Incarceration: The Just Trust Weights In”. Prison Fellowship.org: https://www.prisonfellowship.org/2024/04/second-chances-after-incarceration-the-just-trust-weighs-in/

Proclamation 10721 of March 29, 2024: Second Chance Month (Presidential Proclamation). Federal Register Vol. 89, No. 65 (2024, April 3) pp.22893-22894. Retrieved from: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/04/03/2024-07194/second-chance-month-2024

Public Safety Canada (2022, July 21) “Risk-need-responsivity model for offender assessment and rehabilitation 2007-06”. Retrieved: https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/rsk-nd-rspnsvty/index-en.aspx

Robina Institute (n.d.) University of Minnesota Driven to Discover. Retrieved Aligning Supervision Conditions with Risk and Needs | Robina Institute of Criminal Law and Criminal Justice (umn.edu)

Stein, J., Pranschke, L., Pasternak, E., (2023, January) “Using Risk Assessments in Reentry Services”. Mathematica Progress Together. Dol.gov Chief, retrieved: The Use of Risk/Needs Assessments in Reentry Services (dol.gov)

The White House. Fact Sheet: President Bush Signs Second Chance Act of 2007 (2008, April 9); https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2008/04/20080409-15.html

University of Arkansas of Little Rock. “Community Based Reentry initiative Program; What is the UA of Little Rock Reentry Initiative Program?”. Ualr.edu, School of Criminal Justice and Criminology. Retrieved: Community-Based Reentry Initiative Program - School of Criminal Justice and Criminology - UA Little Rock (ualr.edu)

United States, US Department of Justice. Office of Justice Programs (November 1, 2023) Second Chance Act – Fact Sheet for Fiscal Years 2009-2022. BJA Fact Sheets. NCJ Number 308035. Retrieved: Second Chance Act – Fact Sheet for Fiscal Years 2009-2022 | Office of Justice Programs (ojp.gov)

United States (2024), US Department of Justice DOJ. United States. [Web Archive] Retrieved from the Library of Congress: https://www.justice.gov/archive/fbci/progmenu_programs.html#:~:text=Weed%20and%20Seed-,The%20President's%20Prisoner%20Re%2Dentry%20Initiative%20(PRI),inmates%20contribute%20to%20their%20communities.

Wilson, J., Zozula, C., (2011, November 2), “Reconsidering the project Greenlight Intervention, Why Thinking About Risk Matters”. nij.ojp.gov:

https://nij.ojp.gov/topics/articles/reconsidering-project-greenlight-intervention-why-thinking-about-risk-matter