SPECIAL REPORT: Organizing Forum International Dialogue in Taipei, Taiwan - Labor

Written by Richard Tones

Interesting Differences in Taiwan’s Relatively New Union Movement vs. Canada

In August of 2024 I had the unique opportunity to spend a week in Taiwan as part of the Organizers Forum meeting with amazing activists from the labour, environmental, social justice, and media communities.

After only a week, it would be foolish to suggest that I have a deep and professionally researched understanding of the Taiwanese labour community. To suggest otherwise would be a disservice to their movement. Instead, I hope to give you a glimpse into my experience and draw attention to the things that stood out, and would stand out to Canadian or American labour activists, had they shared this experience with me.

To be sure, most of the challenges they face day to day are the very same. They have varying levels of bad employer behaviour, difficulty engaging members, financial constraints, the need to safeguard pensions, collective bargaining challenges, and a host of other issues our unions in Canada and the United States toil with every day.

What stood out is what was different and unique to me as an activist for over thirty years here in Canada, and as a former member and activist in an international union in both Canada and the United States.

Firstly, their movement is relatively new. This isn’t to say unions haven’t been active for a long time, but the 38-year period of martial law severely limited the growth and political activism of unions, and it wasn’t until 2011 when laws were created and amended to standards like ours. An entire modern legal framework was established covering all aspects of trade unions including their formation, union dues, and collective bargaining.

Although the legal framework is generally familiar, there are also some clear differences, not the least of which is three different kinds of unions under Taiwanese law: industrial unions, corporate unions, and professional unions. Industrial unions are the ones we would be most familiar with and reflective of our own unions. They organize under a central flag and represent workers in most cases across employers, companies, and sectors. Corporate unions represent only workers from a particular employer regardless of their profession, and professional unions represent workers from specific occupations. Although it should be of note that only a few professional unions operate as a union in our context, most of them are legal bodies for the purpose of social insurance matters such as health insurance.

Another of the more interesting differences relates to union dues. In Taiwan there is a minimum percentage of dues one must pay which is 0.5% of a worker’s monthly earnings. An activist we met from the federation that represents workers in the banking sector explained that there is great hesitation in their federation to raise the dues. Any union activist can relate to this hesitation, and in a movement that is so young there has yet to be a union or union leader that has been successful in trailblazing dues increases. The result is cash poor unions that struggle to fund core operations. It is a classic case of chicken and egg; to provide better or more meaningful service, they need to raise dues, but members are unlikely to support dues increases until they see such services. The legislation has seemed to create a standard of the minimum rather than it’s intended purpose. This also results are very small staff groups supporting operations.

Taiwan has a vibrant history of activism, and is by no means an unsophisticated society, but in some ways, it has been stunted by the extended period of martial law that didn’t end generally until 1991, and completely by 1994. This creates another difference when speaking to activists. You can’t help but feel hope and energy, but not the version we are used to, this is the kind that is shiny and new. It doesn’t stem from a passed down responsibility to care for something someone else has built generations before you. It is theirs; they are building it from scratch in relative terms, and it can be infectious.

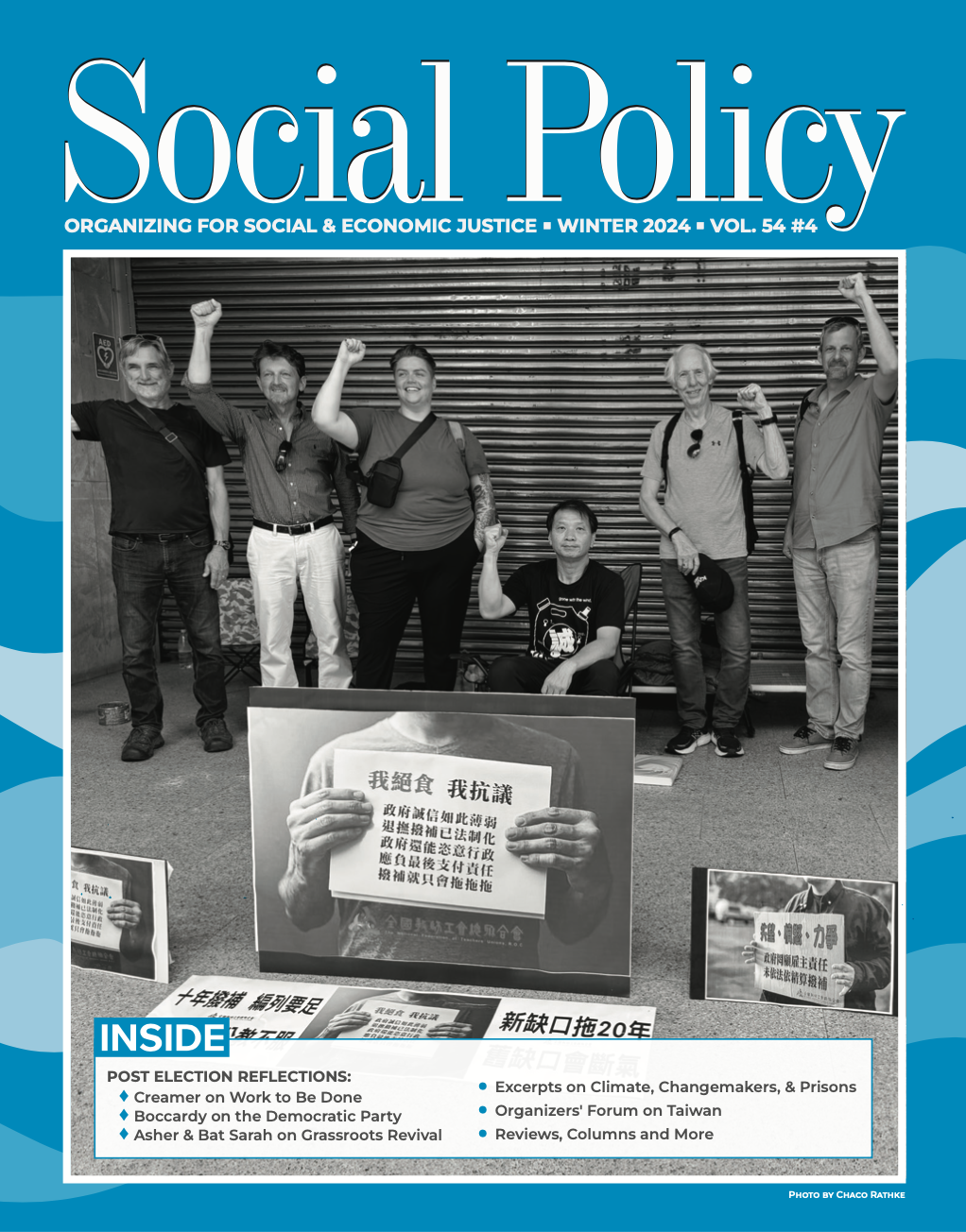

Nowhere did I feel this more than when we stopped by a labour protest at the Taiwanese Central Yuan (Legislative Buildings) in between meetings. The National Teachers Association President, Hou Chung-Liang, was conducting a hunger strike to protest the underfunding of their pension plan and the threat of cutbacks to teacher’s pensions and only ended after he was hospitalized. The issue itself most of us are familiar with, and have fought ourselves, but I can’t recall a single instance where a Canadian or American labour leader has conducted a hunger strike to draw attention to their plight.

Understand I’m not calling for labour leaders in Canada and the United States to conduct mass hunger strikes, nor am I suggesting it as a tool we should be using. Instead, I am using this to illustrate that sense of personal connection to a movement, one of deep conviction and urgency that you feel when meeting many of them. It was a humbling experience as a veteran of the Canadian labour movement.

Taiwan is not immune to deep injustice even with a vibrant labour movement, and the plight of migrant workers also stands out. Like many Asian economies, Taiwan relies upon a massive influx of migrant workers from across the Pacific Rim for domestic workers, services workers, and labourers. To fulfill this need, there are tens of thousands of workers from nations like the Philippines, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Thailand.

The plight of migrant workers is not one we are unfamiliar with, however, it has to be put in the context of a different immigration and citizenship system. There is a clear and articulated policy that generally prevents migrant workers from becoming citizens and their children are not deemed citizens simply by being born in Taiwan. Although there are allowances for highly skilled workers, service and labour sector workers typically come from countries that Taiwan has historically considered undesirable.

Yes, we have migrant workers in Canada and the United States from these same nations, but we also have citizens from these same nations whereas in Taiwan (much like Japan) very few of them actually become citizens and are allowed to formally immigrate.

There is an entire sector that exploits these workers through agency fees, in many cases resulting in workers paying the fee instead of the company that brought them into the country. Employers and the state have a distinct advantage as workers’ status in the country is dependent entirely on their employment.

In order to give these workers a voice, NGOs have been created to represent them both in terms of advocacy and in some cases in the traditional union environment with collective agreements. These are groups working in cramped offices, with stretched resources, with tireless volunteers and staff. These activists also exude that infectious sense of personal connection and of building something from the ground up. They are up against a well-established cultural acceptance of migrant workers and culture-based immigration policy that is not exclusive to Taiwan and is prevalent in South Korea and Japan. They are making progress both on the labour front and political front as more people call for changes to the immigration policy. I will admit as a Canadian that I can’t help but feel a sense of pride when I read about their calls for a more multicultural society.

Most of the things that stood out to me were based on the culture of their labour movement dealing with very familiar challenges in their own way. However, it is difficult to truly articulate the most unfamiliar difference – the ever-present reality of an unfinished civil war.

Unions and their members are deeply impacted, and therefore deeply involved in, the politics of their nation and the larger world. I feel uniquely unqualified to provide a brief history of Taiwanese politics as it relates to China, but I will try to describe the landscape as it relates to the labour movement.

Taiwan has historically been governed by political leaders who still see themselves as the legitimate government of all of China including Taiwan, Mainland China, and Hong Kong. They are simply waiting for the communist experiment to end which would signal their return to Mainland China. They are in fact Chinese Nationalist immigrants to Taiwan who fled during the civil war that followed WWII. Meanwhile, there is another political movement that has moved on and sees Taiwan as an independent nation. Both are unified in the desire to defend Taiwan from Chinese aggression and control, but deeply divided on what happens next.

This kind of political division is reflected in their labour movement with some unions and activists supporting the Kuomintang (the Chinese Nationalists) and others the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). There are competing unions on each side within the same sector and competing national labour bodies. It is difficult to imagine this not being a barrier to a unified labour movement with negative impacts on their effectiveness, growth and influence on the political landscape.

If you spend any time in Taiwan as a labour activist, this ongoing existential crisis may be what stands out the most. It begins the moment you walk out onto the street and see the first of many signs directing residents to civil defence shelters. I will continue to watch with admiration as the Taiwanese labour movement continues their important work