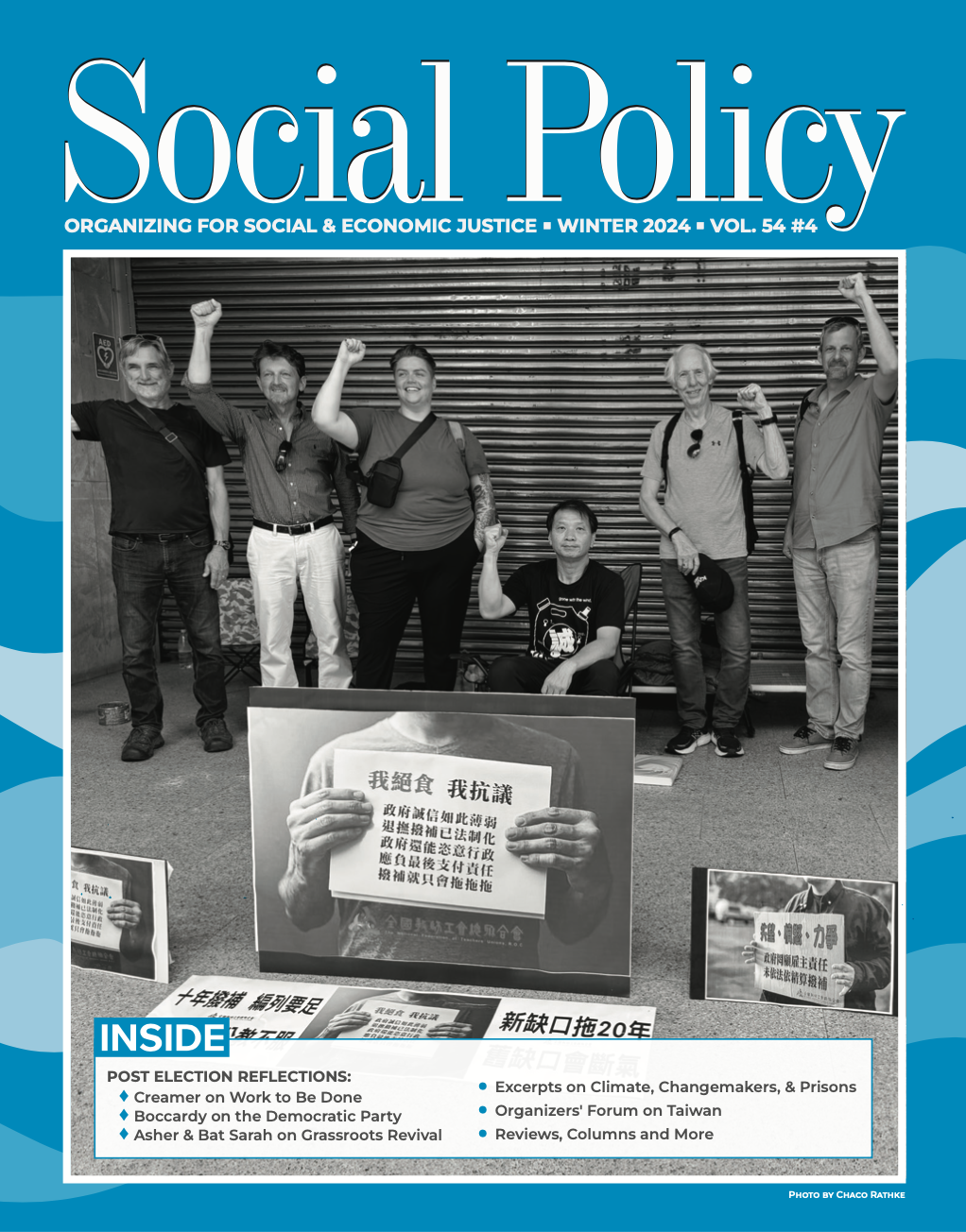

SPECIAL REPORT: Organizing Forum International Dialogue in Taipei, Taiwan - Notes

Written by Drummond Pike

Discovering How Simplistic and Wrong my Perceptions of Taiwan Have Been

It is Sunday morning here in Taipei, and I’m through the worst of jetlag, though still largely confused about time. We are something like 13 hours and a day later than the Bay Area, so back home it is something like 3 am Saturday while 6 am Sunday here. Let us say math skills were never my strong suit.

Though I somehow left behind my Kindle, I’ve finally gotten it up on my laptop and iPhone and am deep into Jonathon Manthorpe’s Forbidden Nation. A truly fascinating history of this place that paints a far more complicated picture than my surface understanding, or most popular US perceptions of this place.

Let me start with the weather – hot and humid, tropical and lush. Taipei gets 50” of rain annually, and this is the “dry” side of the island. For someone trying to nourish a small vineyard in Sonoma County, it would be Nirvana to get 50” a year. We don’t see many old buildings in this downtown area where we are staying, but the few that peek out on occasion show typical tropical decay, mildew and worse, whether constructed of wood or masonry. But this is a very modern city, more akin to Tokyo than New Orleans or Hilo. The train from the airport was as advanced as any in the world, and the stations we’ve seen so far are the same. They make NYC’s subway system look as old and decrepit as it is, by comparison. Like New York in the summer, though, Taipei is air conditioned to the max. You’d want to carry an extra shirt if you expect to be in a building after walking around in the hot humidity.

In ways the US has yet to adopt, Taiwan is pushing the technical envelope. Even the hotel front desk is a bank of computers into which one is expected to enter one’s confirmation number which then leads to the invitation to insert a keycard blank and, voila, you’re in. For our sorry, very tired group of Americans and Canadians, there was fortunately a helper who ushered us through the gauntlet. Similarly, at a restaurant last night, one is ushered to a table where the ubiquitous tablet not only has the menu but is the vehicle for ordering and notifies you as your order is being prepared. Food arrives with little fanfare in no time. It all seems more Star Wars than Bladerunner. This is not to say there isn’t a vital street scene with sidewalk cafes in the steamy heat serving delicious food – decidedly at the other end of the technological range. The juxtaposition is a bit jarring at first.

I’m discovering how simplistic and wrong my perceptions of Taiwan have been. While fascinated by the emergence of Mao’s “new China” in the period following his victory over the Chinese nationalists after WWII, and the retreat of the latter to Taiwan in 1949 as I studied in college, I was woefully unaware of the history of this place or what the 1949 arrival of the Kuomintang leadership meant for this Island just 100 miles off China’s coast. At UCSC, I studied under “sinologist” Bruce Larkin and became familiar the with the emergence of highly centralized power under Mao. (Franz Schurmann and Orville Schell compiled the excellent three-part “China Reader” that anchored our studies with Larkin.)

What I didn’t grasp at the time was the leadership style that characterized Chiang Kai-shek, after he fled with the remnants of his Republican army to Taiwan. He was an authoritarian in every regard. He remains honored in many ways by modern Taiwanese, though it’s a complicated story. The founder of the Kuomintang or KMT, as the party is called, was Sun Yat Sen in the late 1890s while he was living in Honolulu. With the fall of the corrupt Qing Dynasty in 1911, his successor Chiang Kai-shek waged a long campaign through the ‘20s to unify the splintered warlords who emerged from the vacuum. But during this complicated period on the mainland, Taiwan was largely left out of the movement for independence. As the Qing Dynasty fell into disarray, it ceded in 1895 the coastal Fujian province and Taiwan (along with its Penghu islands to the southwest) to Japan which had begun to emulate European dreams of empire. These territories became its first colony and launched Japan’s expansionist period, begun in the mid-19th century Meiji Restoration, that lasted until the end of WWII. Japan ruled Taiwan for 50 years and left an indelible imprint of economic, cultural, and infrastructural development.

Often missed by westerners is Taiwan’s history as a place with a strong, vibrant indigenous people long before waves of Chinese immigration that began during the Ming Dynasty (14th – 17th C.) Late into this period, and extending later into the Qing period, the Hakka people migrated to Taiwan in large numbers. The indigenous Taiwan people of Malay and Polynesian origins were fiercely resistant to these newcomers, as they were to the Dutch and other European forays in the colonial era from the 1500s through to the Japanese hegemony of the late 19th and early 20th Centuries. As late as 1700 or so, Taiwan’s population was roughly split between the indigenous and immigrant populations, though over ensuing decades through the present, the former have dropped to 2-3%. Well after Chinese control of western Taiwan was established, the eastern side of the island was still controlled by fierce indigenous folk who staunchly defended their territory and fought off European and Chinese attempts to assert domain.

A decade before the Qing dynasty ceded Taiwan to Japan, the French colonial enterprise that had subdued Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos (then known as Annam) launched an effort to subdue western Taiwan, putatively under Chinese control. History points to a remarkable Chinese governor, Liu Ming-chuan, who led a tactically brilliant defense forcing the French to abandon the effort. In recognition, Beijing named Liu governor of the island, who followed with a period of reform and development that Manthorpe describes as “a decade of reform and construction that put the island at the forefront of Chinese modernization.” Liu’s leadership preceded for a decade the arrival of Japanese rule (that followed the declining Qing’s 1895 treaty).

Liu set Taiwan on a trajectory of rapid development that, in ways, is reflected in the current ambiguous status of autonomy and progress overshadowed by the mainland PRC’s claims of “one China”. Liu, having defeated the invading French, turned to a focus on modern military defense in ways that eluded tradition-bound Beijing by investing in modern armament. Among many other innovations, Liu created telegraph links all the way to the mainland in 1888. Liu was replaced in the early 1890s weakening the province, so that when Japan won the concession from the Qing, there was only ineffective resistance to their arrival in 1895. The 50-year period under Tokyo’s thumb had important effects on Taiwan – further modernization, ongoing guerilla resistance, the development of an educational system, and a rather corruption-free administration, all giving rise to themes one can see in modern Taiwan. The partisan resistance continued throughout, with the seeding of an intellectual commitment to independence among the “literati” and successful business families that emerged over time.

19th century China was chaotic for many reasons, but chief among them was the introduction of the opium trade by the British looking to by-pass Chinese policy that trade be only in silver. In general, this quasi-colonial period had five European countries and the US vying for “concessions” from the decaying and insular Qing dynasty. The resulting colonial oppression in some ways resulted in today’s deep nationalism in China. But it also led to the post-WWII division of Taiwan from the mainland.

The overthrow of the dynastic system in 1911 led to severe civil conflict as the “nationalists” fought with the communists led by Mao Zedong in the 20s and 30s. The Japanese Empire’s brutal occupation of northern China in the 30s, and a losing hand in the civil war with the nationalists led to Mao’s famous “long march” to a far northwestern stronghold from which the PRC would emerge after WWII to defeat Chiang Kai-shek in 1949. As Mao and Chiang vied for power, the latter somehow gained the support of Roosevelt and the Americans. (There are many stories about how Madame Chiang Kai-shek helped engineer this.) But for many reasons, Mao prevailed, and ultimately a defeated Chiang retreated to Taiwan with the remnants of his army.

Chiang’s 600,000-person army and another 1.4 million mainland Chinese came to Taiwan in the tumult, but they arrived under the leadership of a Kuomintang (KMT) governor, the very corrupt Chen Yi, who exploited more than governed. Chiang had been given control of the island in the post-WWII allocation of Japanese controlled territories while he was involved on the losing side of the long civil conflict with Mao, and Chen Yi was Chiang’s instrument to displace the relatively uncorrupt Japanese system. He did the opposite and inspired the famous February 28th massacre (1947) where Taiwanese rose up against the KMT but were harshly put down with thousands killed by the newly arrived Kuomintang troops. This led to the “White Terror” – an almost 40-year period of harsh martial law, deeply corrupt in almost every aspect of the economy.

Intended to be a place to regroup, the Kuomintang initiated martial law and one-party rule that lasted until early 1987. Chiang’s dictatorship was harshly authoritarian which in part explains the more benign views Taiwanese hold about the Japanese rule that preceded it. While the Japanese in Manchuria were notoriously brutal, they were apparently far less so in Taiwan. At the time of Chiang’s 1949 retreat to Taipei, it was broadly expected that Mao’s forces would eventually replace the KMT, but this notion dissipated rapidly upon the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, and the rapid rise of anti-communist sentiment in US foreign policy circles. Suddenly, the US Navy was patrolling and asserting containment of mainland designs on Taiwan.

According to Manthorpe, during WWII American policy supported the idea of rapprochement between Mao and Chiang in a post-war China, an idea supported by many so-called “China hands” in the US government. This high-minded idea, like so many others, fell by the wayside in the 1950s with the virulent McCarthyism that drove these knowledgeable folks out of influence and often out of a job. The reverberations from those years led to many of the US’s debacles in the latter 20th century, including of course the Vietnam War and all the other “domino theory” driven misadventures. Those reverberations, of course, continue through the current day – with GOP rhetoric often labeling any who disagree with their ideas as “socialist” or “communist,” but that is a different story.

Surveying Taiwanese history, guided by Manthorpe’s Forbidden Nation, leads one to some sense of why the remarkable Sunflower Movement emerged just 10 years ago to alter Taiwan’s political trajectory so significantly. First, long before Chiang brought his army to occupy Taiwan in the hopes of re-invading the mainland, the island had been colonized and ruled by outside powers since the arrival of the Dutch in the 1600s. The colonial experience had never gone well and the serial occupations cultivated a deeply independent sensibility there, in part because of the historic fierce resistance of the indigenous people on the eastern part of the island that carried through to the February 28th revolt against the KMT.

Second, under the Japanese, Taiwan experienced accelerated development and education beyond anything the mainland ever saw. The cultural idea that they can figure it out themselves is reflected in many aspects of life today. It’s a small example, but telling nonetheless. Like many parts of Asia, scooter travel is affordable and constitutes a very large portion of urban transportation. And like many other cities in Asia, this led to congestion and chaos on the streets. As described to us by the head of Radio station ICRT, the government embarked on the almost impossible task of reigning in the beast. It took about 2 years, he said, and involved a massive effort, but the result is remarkable. In large intersections, the orderly manner in which scooters line up in designated boxes separate from cars and buses is amazing to behold. No clogging up the auto lanes and vice versa. No one disobeys the lights.

I am perhaps making too much of this example, but there is something in the Taiwanese sensibility that leads to something like the remarkable Sunflower Movement, described below. To understand this, one must consider how the US has shifted in its posture toward the island, the most abrupt of which occurred when Nixon and Kissinger reversed course and “opened” up direct relations with China. The US didn’t walk away from Taiwan, but it reduced both publicly and militarily its commitment to its independence. As China has grown in its global economic role so dramatically after Mao’s death, Taiwan has risen as a hindrance to its aspirations, especially under current President Xi.

East Asian politics are perplexing to westerners in many ways for both cultural and historical reasons, and that remains to this day. In Taiwan’s case, one thing that is hard to reconcile is the role of the KMT as deeply in opposition to the PRC’s stated goal of reunification and its advocacy for a more open trade relationship with the mainland when it returned to power in 2008. The KMT had slowly loosened the strictures of 40 years of military rule in the late ‘80s and opened up a democratic process in the ‘90s, while holding internally conflicting goals of “one China” and Taiwan’s autonomous self-rule. By 2008, the KMT began a process of expanding Taiwanese business by relaxing curbs on cross-straits trade. Many of the island’s growing companies expanded production into mainland factories and the boom was on. By the end of the decade, the KMT began arguing for further relaxation of trade restrictions in the form of new legislation. What they didn’t anticipate was how this would be received by an emerging generation that was both tech savvy and born into a democratic system that celebrated Taiwan’s culturally held notions of independent identity and centuries long resistance to external control.

So, in 2014 long before the umbrellas were broken out in Hong Kong, an inspiring crew of young activists took direct action by occupying Taiwan’s legislature for three weeks until those in power withdrew the proposed trade agreement. Many repercussions have ensued, and the tensions over economic issues remain vital issues in politics, but the Democratic Progressive Party that supports Taiwan’s independent path just won an unprecedented 3rd term in the recent presidential elections much to the consternation of the Xi and the mainland PRC. With rising global competition between China and the West, one can only guess what is to come for this small, feisty place very much influenced by the Sunflower people now rising into positions of influence and power. China remains Taiwan’s largest though diminishing trading partner. China’s aggression in the South China Sea, particularly with the Philippines, serves as a constant reminder of its long-term goals. How the US manages this complex set of relationships is one of the great challenges it faces for the foreseeable future.

Drummond Pike is a board member of LNRTC and was the founder and CEO of Tides in San Francisco